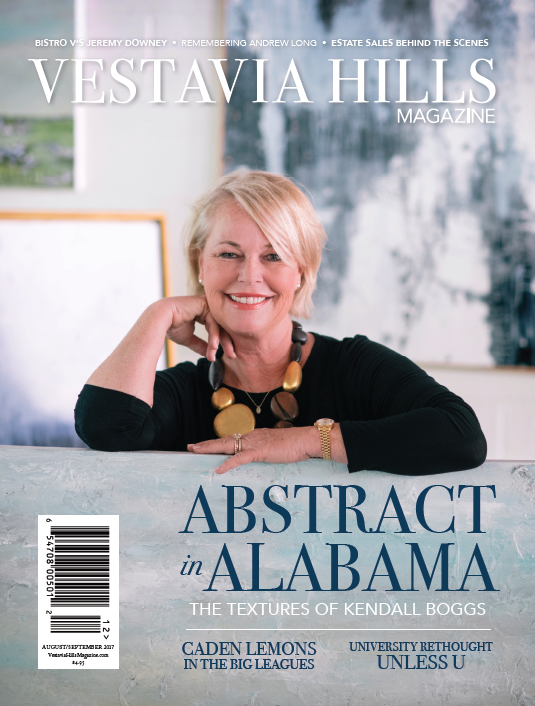

They said she wouldn’t survive. Then they said she’d never walk or live independently. That she’d need special schooling and care for the rest of her life. Somewhere along the line they quit saying what she could or couldn’t do. If anyone had thought Anna Curry Gualano would try climbing the taIlest mountain in Africa, they probably would have told her she was crazy. But it wouldn’t have mattered because Anna quit listening to those people a long time ago.

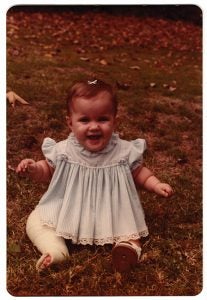

She was born with two broken legs and a dislocated hip, though it would take doctors a while to figure it out. X-rays revealed Anna’s bones had already begun to heal, so they realized her injuries had happened in utero. Finally, after two weeks, the diagnosis came: Osteogenesis Imperfecta, or OI, also known as Brittle Bone Disorder. Affecting one in 15,000 people, OI is a genetic condition that stems from a lack of collagen in connective tissue. It is characterized, mainly, by bones that break easily or without a specific cause.

It was a miracle that Anna, now 38, had even survived being born. As a child, she broke a bone putting on a Sunday dress. Sneezing could break her spine. By the time she was 10, she had logged more than 100 broken bones. Somewhere along the line they quit counting.

Anna’s parents, Marga and Ashley Curry (the current mayor of Vestavia Hills), moved to Birmingham in order for their daughter to be treated by one of the country’s only pediatric OI experts. He gave them two options: keep Anna in a wheelchair to keep her from getting hurt, or let her live a normal life and address the breaks as they happened. They chose the latter, though they probably thought they’d have a little more say in the matter when it came to what, exactly, she’d try.

“In Vestavia, in the ‘80s, girls softball is where it was at,” Anna says over coffee at O’Henry’s. “Everybody played softball and so I wanted to do it.” She was 7 and had seen enough of her older brother’s games and baseball trophies to know she wanted in on that, too. Her parents said no. But Anna didn’t quit.

One day, she caught her mom away and talked her dad, an FBI special agent, into taking her to buy a pair of cleats. “So my mom gets home later that night and I’m already in bed. My dad has to sort of fess up to what he’s done, and so my mom says, ‘You have to go in there and wake her up and you have to tell her that she can’t play softball.’ So they go in, and I’m asleep with the cleats,” she says laughing.

One day, she caught her mom away and talked her dad, an FBI special agent, into taking her to buy a pair of cleats. “So my mom gets home later that night and I’m already in bed. My dad has to sort of fess up to what he’s done, and so my mom says, ‘You have to go in there and wake her up and you have to tell her that she can’t play softball.’ So they go in, and I’m asleep with the cleats,” she says laughing.

Anna’s parents decided if her doctor said she could play, then they’d let her. The truth is, they never thought he’d say yes. “He said, ‘Well, if you understand the risks and you’re willing to live with them, I don’t see why you can’t play,’” Anna says, stills triumphant. “So I got to play.”

It was a big responsibility to give a 7-year-old. “That first season I broke both of my legs trying to stretch a single into a double,” she says, with a laugh that surely wasn’t as easy to find when she spent the rest of the long, hot, summer in two leg casts, unable to go to the pool.

“Even at 7, I understood the consequences,” Anna says. “I knew what it meant to break a bone. Anybody with OI understands that it’s a vicious cycle (breaking bones and waiting for them to heal), but I also knew that the benefit of doing it and participating in a team, feeling like I could knock the ball out of the park—all of that stuff was far more important to me than the temporary downside of having a broken bone. I knew what that was like. So for me, it was absolutely worth the risk.” And she played two more seasons, until the league switched to girl’s pitch, which was just too dangerous since a hit in the chest could kill her.

But according to Anna, those three years changed her life. She credits girls softball in Vestavia for setting the tone for the rest of her life. “I WAS a part of the team and I DID get to do a sport that I never thought was going to be possible for me, and it just sort of proved—solidified for me —that man!, if I really DO want to do something, I CAN.”

“Kilimanjaro?” Anna says when I ask. “That was just the next in a series.”

“Kilimanjaro?” Anna says when I ask. “That was just the next in a series.”

Anna first got the idea to climb the volcanic peak in Tanzania while she was in law school, but the timing wasn’t right. A few years later, when she broke her leg playing football on the beach (I know, right?), she was laid up in the hospital in Atlanta, finding it harder to recover than it had ever been before, and she knew she needed a goal, something for her to focus on.

She waited until her parents came to take her out on her birthday, and AFTER they’d ordered, to tell them her big idea. She sat there, in her wheelchair, waiting for their reaction, when her dad said, “When do we go?”

It took her three years to get there. First, she had to do therapy just to walk again. After that, she had to train since climbing Kilimanjaro means hiking 10 to 15 miles a day. For a woman who can break a bone stepping wrong off a curb, climbing a 19,341-foot mountain that starts in a rainforest with roots and vines that are easy to trip over, shifts to rocks that roll under your feet, and ends in boulders and ice, was a serious undertaking. But she did it in 2009. Even more amazingly, she didn’t break a single bone.

Then, she married a fellow lawyer who had just finished through-hiking the Appalachian Trail and understood a thing or two about goals, himself. Anna always knew she wanted a family, but for someone with OI, giving birth can have dire consequences. “A couple doctors told us that it would kill me,” she says. “I didn’t really believe that.” She did think the strain of carrying a child would cost her her mobility, but she was more than willing to make the trade. “There are some things that are more important,” she says.

Six years ago, she had a 6-year-old son Luke, delivered five weeks early via Caesarean section. She had breaks in her spine and ribs, but to hear her tell it, “I did pretty well with that pregnancy.”

Six years ago, she had a 6-year-old son Luke, delivered five weeks early via Caesarean section. She had breaks in her spine and ribs, but to hear her tell it, “I did pretty well with that pregnancy.”

You’re probably not surprised to hear she didn’t settle for one child. She and her husband welcomed a daughter, Charlie, three years ago. After all, she “just knew our family wasn’t compete.” Anna had heart and lung difficulties during that pregnancy, and now says she’s perfectly satisfied with two.

What she isn’t satisfied with is sitting around doing nothing. Some days she uses a wheelchair to minimize the stress on her leg bones, and though pain is a regular part of her life, she reports having children has not taken the toll she expected. In fact, she and her husband, Mark, have participated in the Callaway Gardens Triathlon three times and are planning to do it again next June. As in the past, they’ll raise money for the Jamie Kendall Fund for OI Adult Health, named for a friend who had OI and died a few years ago during a routine operation from anesthesia.

Aerobic fitness is one of the best things Anna can do for herself since lung and heart problems are a common complication from OI because all the body’s organs need collagen to work properly. For the first time she’s thinking about using a racing chair for the running portion of the course.

“I don’t see the chair as this kind of cage anymore. I did when I was a kid. I really didn’t like being in a chair. Now, I’m so much faster in the chair,” she says, laughing. “I still am trying to be as mobile as I can, but my goal is fitness, however I can come by it. I would like to stick around awhile for my kids.”

I’m pleased to report Anna has given up on playing beach football. And water skiing.

Parenting Anna

Anna’s own daughter recently dislocated her elbow at preschool, and as Anna sat in the emergency room at Children’s of Alabama, worrying over her daughter’s elbow, Anna thought about the hundreds of broken bones she’d had growing up, and realized her mother is a saint. She called her up and asked “How did you it?” So we thought it would be fun to ask Anna’s mother, Marga Curry, about what it was like parenting such a force of nature. “She always was,” Marga says, “a force of nature.”

Anna’s own daughter recently dislocated her elbow at preschool, and as Anna sat in the emergency room at Children’s of Alabama, worrying over her daughter’s elbow, Anna thought about the hundreds of broken bones she’d had growing up, and realized her mother is a saint. She called her up and asked “How did you it?” So we thought it would be fun to ask Anna’s mother, Marga Curry, about what it was like parenting such a force of nature. “She always was,” Marga says, “a force of nature.”

ON SOFTBALL

Yes, they really thought the doctor would say no. “A lot of it was trying to teach her to make good choices.” But the night in the hospital after breaking her legs in the softball game, Marga says Anna told the coach, “I’d do it again, tomorrow.”

What Anna didn’t tell us (but her mom was happy to) was that the Vestavia Girls Softball League established the Anna Curry Award that they give each year to the player who shows the most courage.

PREGNANCY

“It was terrifying!” Marga says of when Anna got pregnant. But it’s not like she could do anything. “A lot of things she does, she doesn’t ask.”

LAW SCHOOL

Another thing Anna didn’t tell us but her mother was more than happy to share was that the University of Alabama Law School created an award in Anna’s name given each year to a law student who has shown outstanding leadership and service to the law school.

KILIMANJARO

What do you do when your daughter with OI tells you over dinner (while in a wheelchair from playing football on the beach) she’s going to climb a mountain? “You roll your eyes and say, ‘Oh, Anna!’ and then you get a drink.”

WHAT’S NEXT

“I’m almost afraid to ask.”