Months later, the Pizitz Middle School could still recall the faces—faces not unlike their own, yet with a far different life story than theirs. They were the eyes and smiles of kids without access to fresh water, and the images that stayed in their minds as they learned that around 800 kids die every day from lack of clean water and as they watched an eighth grade football player carry a 5-gallon, 40-pound jug across their school’s gym—not an easy feat for even an athlete, but a daily chore in countries like Sudan and Uganda.

Sixth grader Ethan Raley called this assembly “wow” moment, thinking back to the speaker from Birmingham-based Neverthirst in the fall of 2017. “I knew about people not having access to water, but I didn’t realize it was that bad,” fellow sixth grader Virginia Dove says. “It made me want to participate.” And participate they did—all as a part of a yearlong focus on water at the school dubbed Be the Drop that Fills the Bucket.

One part of it was raising money to fund a well in northern Uganda by the end of the school year. Throughout the year Pizitz students bought tickets and baked goods at a robotics race, band concert, faculty-student volleyball challenge and a movie event. The Advanced Art and Eco Club made leaf silhouette bowls, the yearbook staff designed a T-shirt, and one seventh grade “team” of classes held a “change war.” “I think you could tell people were motivated when we did fundraisers to raise money,” Ethan notes. ”It made me happy to realize how many people actually cared about it.”

Each penny they raised was a drop in the bucket, if you will. And as students saw photos hanging in the hallways similar to those they had seen in that first assembly, they remembered just what each penny was for. “When you walked past (these photos), it made you think about it,” eighth grader Corbin Maher says.

Each penny they raised was a drop in the bucket, if you will. And as students saw photos hanging in the hallways similar to those they had seen in that first assembly, they remembered just what each penny was for. “When you walked past (these photos), it made you think about it,” eighth grader Corbin Maher says.

The idea for the water project started in 2011 when sixth-grade science teacher Diane McAliley told students about wells she’d seen during a summer she spent in South Sudan. These students later made presentations to share what they had learned with other classes. One student in particular had been unmotivated in her class all year, but then this project came along. “It woke him up and made it come alive,” Diane says. “He ended up making straight As the rest of the year.” That memory never left her.

So when she came to Pizitz four years ago, Diane had a dream of a yearlong water focus stretching through academics and beyond. “We were aiming to get the kids to be aware and make a difference,” she says. ”Kids this age want to know their life matters.” Grant money from the state funded water testing kits, class sets of books and other equipment for academic components, but most of the ideas came from within the school. Diane had encouraged fellow teachers to dream big about how to embed the theme in their standards, and then the students later dreamed up their own fundraisers.

In sixth-grade science students took water samples from a nearby creek and grew cultures to test it. “The water was clear but when we tested the water there was a lot of bacteria,” Virginia recalls. “(In these African countries) the water looks really dirty and it’s even worse than that.”

In sixth-grade science students took water samples from a nearby creek and grew cultures to test it. “The water was clear but when we tested the water there was a lot of bacteria,” Virginia recalls. “(In these African countries) the water looks really dirty and it’s even worse than that.”

This class also designed and built their own water filters in plastic bottles using hay, gravel, sand, charcoal, cotton balls and coffee filters in plastic bottle. Likewise, eighth graders tested tap water for pollutants, pesticides and bacteria—and balanced equations with their findings.

After learning about body systems, seventh graders acted as “doctors” as they researched and diagnosed foodborne illnesses based on patient cards they were given, and then they had to find a current news article about their particular issue, which brought news of e coli outbreaks or flesh-eating bacteria closer to home. “It opened up their eyes to situations that could happen in their lives and the lives of people they know,” teacher Aimee Farrar says. “Within the context of the well project it allows them to see how things we can do can impact the whole world.

In social studies, students talked about how ancient civilizations grew up near water and collapsed in droughts. A coding class made games to educate about water issues. German students discussed the lead crisis in water in Flint, Michigan, and wrote letters to an elementary school there. In English, some students read A Long Water to Water, a book set in Sudan, and wrote dual narratives in the same style as the book.

Aimee also shared in social studies classes about a mission trip she took to Malawi and the water issues she saw there. “My biggest soap box is the value of education and how lucky they are to get to go to school,” she says, noting that often it takes kids so long to transport water that they don’t have time for school. “I share some stories of the orphans who mention no food and no clothes and the only way they knew to get out was to get an education.”

Likewise, along with academic water projects came a vision for something bigger at the school. “You want (students) to have a chance to focus on things that are bigger than themselves,” Diane says. “While sometimes we think (these students) are just looking at themselves or their friends, they are so generous and excitable about looking out for other people. You want them to take the idea and make it their own so it comes out in authentic situations.”

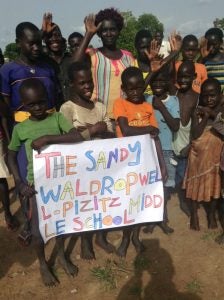

By the end of the school year, the school reached its goal. With the $8,100 they raised, Pizitz students funded a refurbished well in Uganda that had been broken since the ‘80s. As Diane would say, it was “well done.” The well now serves 100 households, and most of them make five trips for water a day. That’s 500 buckets a day, and if the life of the well is 20 years, that’s “4.56 million buckets of water we raised by having fun and learning some stuff,“ Diane says. “When you provide water, you affect total life change. I can’t think of anything greater to accomplish at a young age. It’s empowering.” The well now bears the name of Sandy Waldrop, a Pizitz librarian who was diagnosed with a lung condition right after the Neverthirst assembly last fall and passed away by the end of the year.

By the end of the school year, the school reached its goal. With the $8,100 they raised, Pizitz students funded a refurbished well in Uganda that had been broken since the ‘80s. As Diane would say, it was “well done.” The well now serves 100 households, and most of them make five trips for water a day. That’s 500 buckets a day, and if the life of the well is 20 years, that’s “4.56 million buckets of water we raised by having fun and learning some stuff,“ Diane says. “When you provide water, you affect total life change. I can’t think of anything greater to accomplish at a young age. It’s empowering.” The well now bears the name of Sandy Waldrop, a Pizitz librarian who was diagnosed with a lung condition right after the Neverthirst assembly last fall and passed away by the end of the year.

Even as this dream has been brought to life, Diane is dreaming up future themes (the sun, perhaps?) and hoping to plan a trip to the well Pizitz funded in Uganda with other teachers and document it with virtual reality technology they could bring back to for Pizitz students to experience. And students are left dreaming too. Parker Fulton wants to bring shoes to people in countries like Uganda who don’t have them. Noah Evans is researching ways to desalinate salt water to bring fresh water to communities. And “being the drop that fills the bucket” is in the vocabulary—and mindset—of countless students.

The Sandy Waldrop-Pizitz Middle School Well

Completed February 2018

Completed February 2018

Kogbo, Yumbe, Uganda

Through NeverThirst

Testimonies from Local Residents:

“My name is Silvia Karabia and I am 40 years old. For a long time we were collecting water from a stream far away. We would walk almost 4 miles to the water source and it would take us more than 2 hours a day. The taste of the water from stream was very bad. Sometimes we boil but sometimes no because it take long time. We have been effected by many waterborne diseases like diarrhea and vomiting after our well broke many years ago. We thank Neverthirst and the people who helped us get this well. Now we have clean water near our home and will not suffer from many diseases. Thank you.”

“My name is Mauals Yabu and I am 37 years old. We know how much God loves us because we have a borehole now. We do not have to drink from stream far way and can collect water near our home. We will not suffer from diarrhea anymore. God bless you!”