Coach Wayne Wood first saw the mural when he was driving on Columbiana Road. Standing tall boasting blues and golds, there’s no doubt it’s the focal point of the school building Wood saw. Wood didn’t teach or go to school there, but it was just a curious fascination of his.

To some passersby it might just look like a geometric, painted wall on the side of an old school, but it’s got a story— a 50 years and counting kind of story. The mosaic is made up of 138,480 tiles that have observed thousands of students walk through the halls since 1965. Originally installed for W. A Berry High School, this unnamed mural has become “The Berry Mural” to those who’ve been close to it, but now Vestavia Hills can call the artwork part of its home. The building is currently transitioning into Pizitz Middle School for the 2019-20 school year, encasing the mural behind fences and construction for right now.

Wayne Wood stands at the old Berry stadium named in memory of Coach Bob Finley. Vestavia Hills City Schools will keep the stadium name in addition to the mural.

On his way to becoming the unofficial Berry mural historian, Wood, a 30-year teaching and coaching veteran at Simmons Middle School, found the simple beginnings of the mural in a Birmingham News article about Kerry Buckley, the senior class president of 1965 who drew the mural design. “Probably because he was class president, he looked at things differently than the normal student,” Wood says of the depth of the design. It represents a timeless quest for education, made up of different talents and pursuits. What’s held by each figure corresponds to each field of education: the laurel wreath represents athletics, the triangle represents mathematics, the palette and brushes represent the arts, the atom represents the sciences, and the quill and scroll represent the humanities. The torch above the figures represents the illuminating light of knowledge.

Wood has always looked towards the future of the mural, too. After shifting from the high school to Berry Middle School, then to being vacant and used for “this and that” as a Hoover community space, he and others, including a few Berry High grads, would go clean up the grounds, including Finley Stadium and the area around the mural building. “I just developed an affection for the coaching staff and the high school,” Wood says, reflecting on his ties to the building. Seeing the grounds covered in broken tiles, he saw the need to keep this piece of art alive. Now, Vestavia Hills City Schools will be that force, inheriting the mural and making it a part of their story, their own quest for knowledge.

In 2016, the Vestavia Hills school system, in need of another building, announced their plan to buy the Berry campus, leaving many graduates and people like Coach Wood unsure of what would happen to the mural and the stadium named for the beloved and iconic Coach Bob Finley. Former Superintendent Sheila Phillips answered the call, stating that the mural and stadium would be maintained to respect the embedded tradition. And as construction on the building continues, the projects across Vestavia schools are scheduled to be completed in June 2019, says Dr. Patrick Martin, assistant superintendent of operations and services for Vestavia Hills City Schools.

The tiles come from a different time and a different school, but the mural’s joining a new legacy. “This mural belongs to a lot of people. It belongs to the people who went to school there. It belongs to the faculty members. It belongs to the ages, to education,” Wood says. “A lot of alumni live in Vestavia now. There is a connection to Berry and the mural that’s not just Hoover.”

As the building becomes Rebel grounds, it will always have a place in the hearts of graduates, especially those like Ashley Moran, a Berry High grad and a Vestavia resident who will soon send her two youngest children to the new Pizitz building. She’ll tell you that Berry is “a big part of my family heritage.” After all, two of her aunts graduated from Berry before she did in 1992 too.

Berry graduate and Vestavia mom Ashley Moran brought her kids Abigail and John Michael to the visit campus where Abigail will start middle school in four years.

As a high school student, Moran went to mural building for Advanced Studies Team, the school’s gifted program, as well as for Mrs. Seller’s art class on the bottom floor. A member of the color guard, she was at every football game, too. “It was incredible to be able to go to the games and see how excited everybody was about it,” she says. Berry went to the state championship her freshman year with senior player Stan White, who would go on to be Auburn’s quarterback.

Moran also remembers her older sister’s parking spot being close to the mural and always passing it to go to the stadium, along with all the other students. “Everybody used to go to the games just to be excited for the team. It didn’t matter if we won or lost,” she says. “We just wanted to be a part of it.” Now, her Vestavia West second grader Abigail and five-year-old John Michael will get a piece of her high school pride when they go to middle school at Pizitz with the mural nearby. “I’m glad to see Vestavia bringing it to use as a school again,” she says. “I didn’t want it to get torn down because the mural represents Hoover and now Vestavia.”

Not only does Vestavia now get the physical building, but they’ll also get the chance to adopt the meaning behind the tiles. “The mural was something different. When you walked on that campus, you knew you were at a special place,” Larry Giangrosso says. Now principal at Spain Park High School, he got his first job at Berry High School as an English teacher and baseball, football and basketball coach and worked there from 1975 to 1990.

Everything Berry did, and the excellence the community craved, corresponded with what was on the mural, Giangrosso notes. “It was a large part of our success even though we didn’t know it then,” he says. “You’ve got to fit into the mural. I used to tell students that. There’s a reason why there’s not only one figure on that mural. Each one represents something different, and that was us.”

The unity between figures on the mural represented dynamics between Berry students on the daily. On a rainy day one spring, Giangrosso remembers students having to crowd into the gym to practice, with theater students holding a dress rehearsal on the stage, baseball players throwing on one side of the floor, wrestlers on their mats at the other side, cheerleaders in the lobby— a medley of different people who you wouldn’t imaging crossing paths. “Everyone was working as hard as they could, and we were all happy, the 500 of us in this one room,” he recalls. “Everyone belonged, and everything was important.”

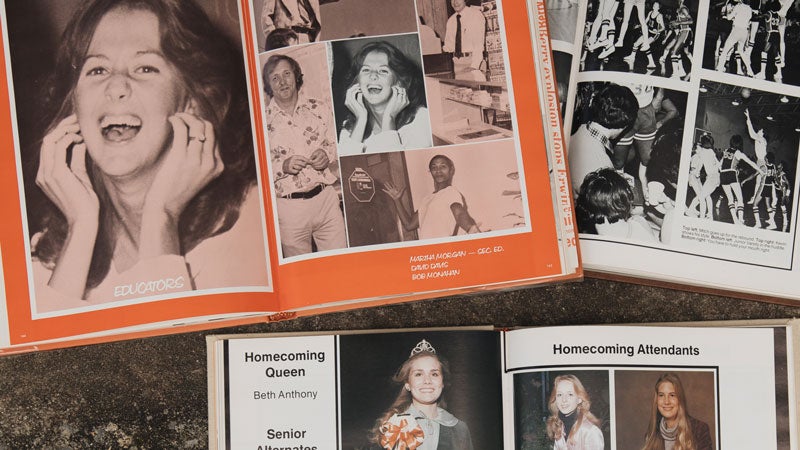

A few yearbooks from the ‘70s showcase some of the glory days of Berry High.

Melissa Hays remembers the love people like Giangrosso had for the high school and its mural when her mom was English teacher at Berry when she was little. “I remember it being such a focal point of the school and what my mom told me what it represented,” Hays says. She’d go to help her mom (Melody Greene, now Assistant Superintendent for Hoover City Schools) set up her classroom in the summers and later entered Berry Middle School as a sixth grader in 1996.

The love for the mural, the favorite photo-op for the high schoolers, was lost among most middle school students there, as Hays remembers. But the mural building, separated from the rest of the school, was still where she remembers wanting to be since it was the eighth-grade building. “The mural is what set that apart and made it unique. It felt original,” she says. “The whole building changed when they made the middle school, but that never changed.”

Wood is excited that the mural will greet a new, young generation to begin its Vestavia story. “I think it’s very unifying,” he says. “I know there are rivalries, but this is a common denominator. This mural doesn’t depict the cities. It transcends time before and afterwards in how it represents education.” He hopes to see an official historical marker on the mural one day, and likely future Pizitz students will memorialize it as well in their own photos. The question is just what hashtag of their own they will give it.