As I look out to the lush green panorama from Shades Mountain from what is now Vestavia Hills Baptist Church, I imagine I’m back in the 1920s. What I see before me is blanketed in dogwoods and wild azaleas, and in the manicured gardens behind me a party takes me back even centuries before. Vestal virgins are dancing in white tunics. Pompey and Cataline don Roman helmets and swords, as they walk past Villa Cleopatra, home to a beloved dog. Peacocks are strutting to show off their electric plumage. As dusk turns to dark, the party doesn’t dim. The estate lights up with glitter and glitz. And at the center of it all, former Birmingham mayor George Battey Ward stands in costume, framed by his epic four-story temple-shaped home rising up behind him.

Ward was a true Renaissance man. The flamboyant millionaire was a philanthropist and lover of Shakespeare and Plutarch. A successful investment banker, he had served as mayor of Birmingham twice and as president of city commission once, but today he’s most remembered for the temple he created on Shades Mountain and named by pairing “Vesta,” goddess of the home and hearth fire, and “via,” Latin for roadway. As even a quick look at the legacy of Vestavia (namesake of Vestavia Hills) reveals, there’s no doubt where he earned the reputation of being “as mischievous as a leprechaun” and “as eccentric as the wind.”

Roman Relics

Roman Relics

On a trip to Europe in 1907, Ward, a lover of classics and Roman history, had brought back a small model of the Temple of Vesta, which was destroyed in the fifth century in Rome. It was this model that became the inspiration for his home to be built on the 20 acres on the crest of Shades Mountain he’d bought in 1923. Architect William Leslie Welton of St. Louis, a graduate of MIT, designed the temple with multi-hued sandstone quarried locally instead of the Roman marble seen on the original structure, and it was completed in 1925.

Writing in 1935, Mittie Owen McDaniel illustratively described what she had seen at Ward’s “bachelor abode,” overlooking the valley she said you might liken to the “seven hills of Rome.” “High on the crest of a ‘Heaven-kissing hill,’ wrapped in mists of early morning, Southern sunshine at midday, and the light of glorious sunsets at eventide, ‘Vestavia’ sits enthroned,” she writes. “Each window in this temple-mansion frames a panorama of alluring landscape in all its reaches of changing beauty. The grounds stretch out in velvet greenness.”

Vestavia’s upper 10 acres boasted well-tended manicured gardens, pools, fountains, blossoming vines, trees, shrubs and thousands of flowers. Across the road, the remaining 10 acres were left “rustic” with winding paths for visitors to stroll and acted as wildlife sanctuary. On the upper 10, a wrought-iron entrance led to rose gardens, a sunken garden, and “the sparkling fountain spraying down through the feathery foliage and breaking into a thousand diamond drops upon the pool, give it all a fairy-like, ethereal grace.” Around the grounds marched a flock of peacocks “sweeping their gorgeous plumage.”

As to the temple itself, doors off the two-story portico were copied from a cathedral in Milan, Italy. Inside a dining room seated 42, and a circular staircase led to the second floor with sleeping quarters and a bath with a multi-headed shower. Massive fireplaces were identical on each of the three floors, with marble lamps from Italy anchoring both ends of the mantel in the living room. Nearby bookcases displayed Roman statues of course, and the curtains were Gorgette velvet in the winter and filmy gold in the summer. A miniature “Louvre” of postcards showed off every painting in the Paris gallery.

This photo courtesy of Vestavia Hills Historical Society. All other photos courtesy of Vestavia Hills Baptist Church.

The Stuff of Legends

Over time, the temple became known for far more than its architecture, as longtime Vestavia Hills resident Frances Poor has documented from studying all 24 of Ward’s scrapbooks. Ward’s servants dressed like Roman legionaries with helmets and swords, and Ward gave them Roman names: Pompey, Scipio, Lucullus and Cataline. Ward himself loved a parade and was often seen in costume, too. He also built pillared, temple-like houses for three of his many dogs: Villa Nero, Villa Plato and Villa Cleopatra, all located on his version of the Appian Way. His Mediterranean Sea was a pool with water hyacinths, lilies and ferns. Statues of famous Romans were places in fountains, in pools, on pedestals, everywhere. “Some people thought he was ‘Battey,’” Poor writes.

Ward hosted parties for hundreds and threw Roman festivals complete with dancing vestal virgins dressed in white tunics. On Sundays he opened his home to visitors from the public to see his peacocks strut on the lawn. One day in June alone, 8,000 people visited the temple. A light on the property turned green to signal if it was open, red if closed and white if a party was going on. Ward also hosted a Roman dinner for Latin students at Ramsay High School, a Blossomtime Festival with pageant queens and event after event. He held public concerts and dances where he’d roll out his piano and play, or broadcast music from his Victrola with an automatic record changer.

At sundown, the property was no less stunning thanks to more than 1,000 lamps. “At night when illuminated, Vestavia glittered like a huge constellation high above the city” Poor writes. In fact, Ward was “the largest rural electrical customer in the state,” according to the Alabama Powergram.

Over the years, the Vestavia temple welcomed George Washington Carver, Better Homes and Gardens editor Elmer Peterson, and Arnaldo Mussolini, brother of the Italian dictator. Gone with the Wind author Margaret Mitchell praised the home in a letter to Ward: “So you live in the lovely Greek temple on the mountain top! I have passed it so often and admired it so much. The proportions of the house are so lovely and it is so well situated to show them off.”

Former Vestavia Hills Mayor Sara Wuska recalls a story she heard from John Eddings about growing up near the temple. “In his courting days, the drive around the Vestavia Temple home was the preferred lovers’ lane of the era,” she recounts with a laugh. “George Ward learned about his night visitors, and he installed speakers and would play live music to entertain them. The mothers found out about it, and if Johnny Jones didn’t get home by curfew, she’d ring up George and say, ‘George, you tell Johnny Jones I said to get home!’ And he’d get on that loud speaker and say ‘Johnny Jones! Your mother says to come home!’”

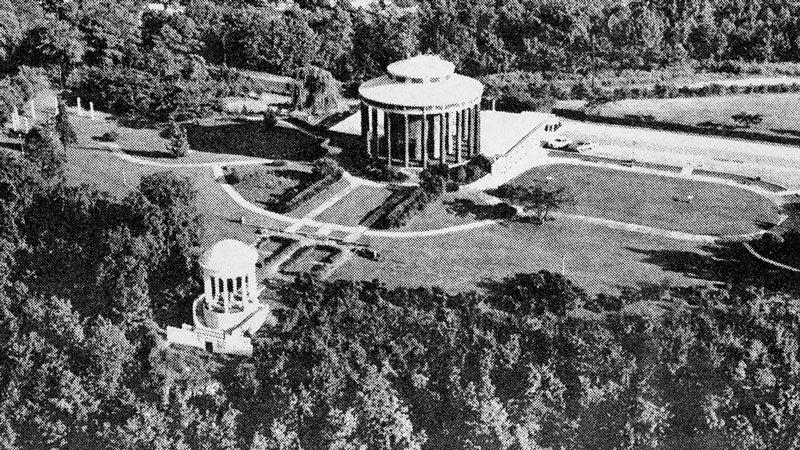

In 1929 another temple joined Vestavia on the property, this one a replica of the Temple of Sibyl, a Cumaean prophetess identified by Aristotle, on a promontory overlooking the valley. It was to be a monument to Ward’s final resting place as he wanted to be buried in cave beneath the temple. The circular structure was built of red-hued, steel-reinforced concrete with a large dome supported by eight pillars. It was not painted white until the 1940s.

However, the festivities came to an untimely close. In 1935 Ward was diagnosed with terminal throat cancer and had a stroke, and his brokerage business had declined in the Depression. He died in 1940 at age 73, leaving the temple and upper 10 acres to three nieces and lower 10 acres and Sibyl to the city of Birmingham. The nieces didn’t want the building, so they liquidated it to pay Ward’s debts. The Jefferson County laws wouldn’t allow for his burial plans, so Ward was interned at Elmwood Cemetery instead.

Shades Mountain Destination

Shades Mountain Destination

As World War II was waged on two fronts, the property fell into disrepair until Charles Byrd, realtor and president of Byrd Real Estate Company, purchased it in 1947—a year after he had started developing the first subdivision in the hills surrounding Vestavia (what would become “Vestavia Hills”). After $200,000 of renovations, he reopened Vestavia in 1949 as a tourist attraction with posh restaurant and an outdoor tea terrace.

Vestavia Gardens Restaurant served Southern fare on the gardens with goldfish ponds and views. Imagine it as the Shades Mountain equivalent of The Club, complete with Mrs. Ewing Steele’s orange rolls, now famous at The Club. Ann Cavaleri, a current Vestavia Hills resident, remembers her parents and her soon-to-be-husband’s parents meeting for the first time at the restaurant in 1953. Her husband’s parents dined there regularly, and she recalls it being a “very nice restaurant” with tables on either side of the temple itself—all very “light and bright and very cheerful.” With the reopening, symphony concerts playing, ballets and a yearly rose festival with a queen crowned returned to the estate too.

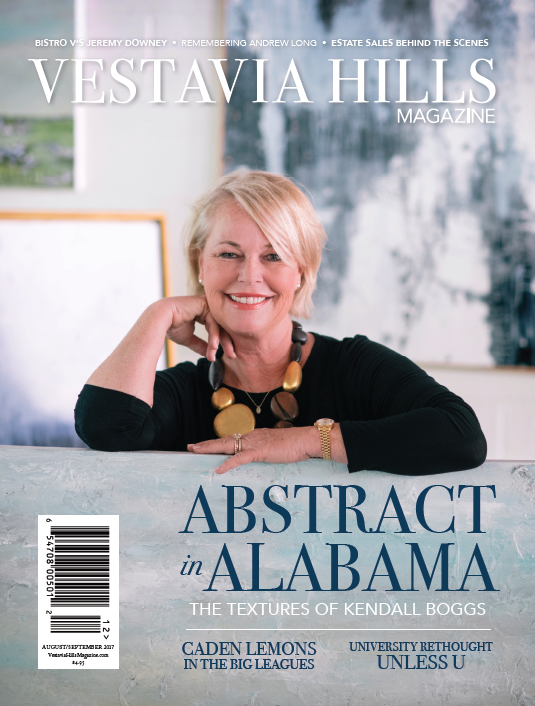

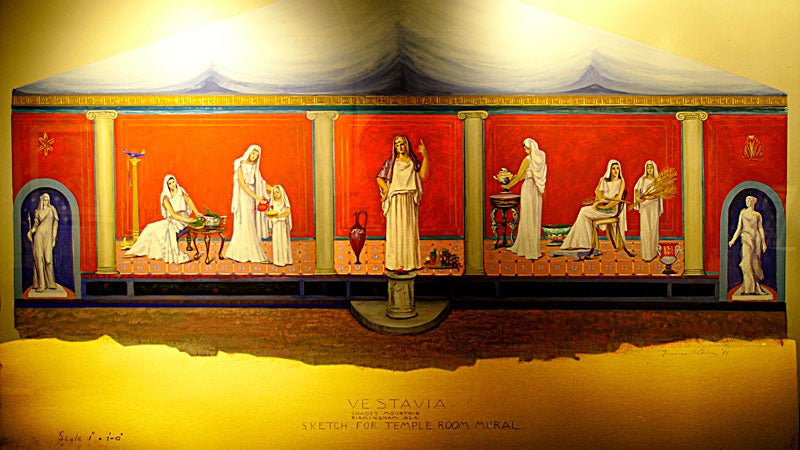

As a part of Byrd’s renovations, the temple’s fourth floor became a “Temple Room” where New York artist Frances O’Brien painted a giant 88-by-13-foot mural of Vesta, Roman goddess of the hearth, and her six priestesses with seven local socialites used as models (see a photo of this above). Seven other statues of Roman goddesses were placed throughout the room. In 1950 Byrd also added a pergola of eight marble columns that Robert Jemison had given him from the old People’s Bank Building. These were to be used as backdrops for outdoor theatre productions. Today, these columns mark the entrance to Vestavia Hills from Hoover on Highway 31. Ultimately Byrd’s business failed, but not without leaving a mark on Birmingham.

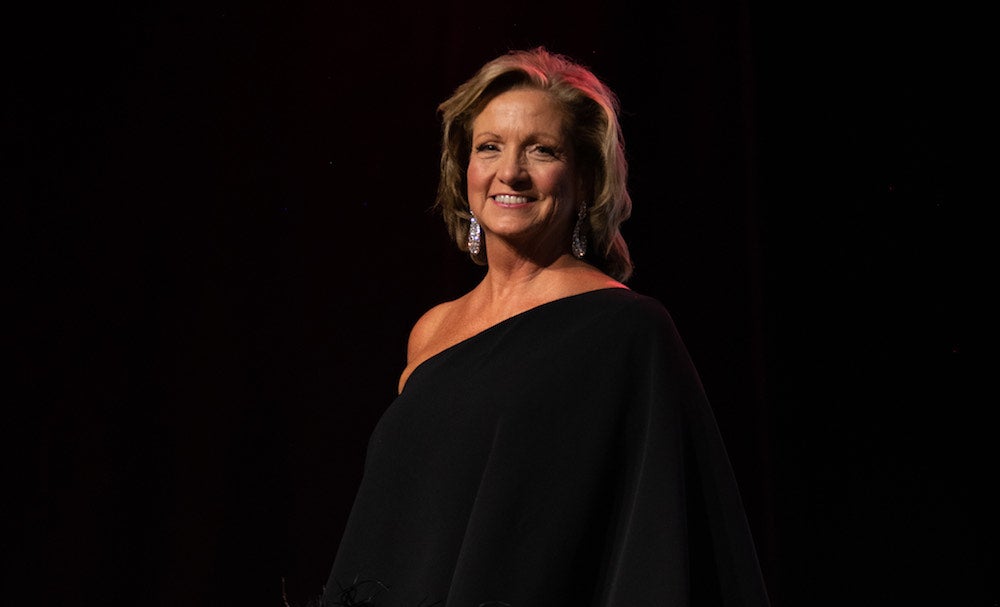

Photo by Megan Tsang

Likewise, Sibyl would also find a new home at a roadside park marking the other entrance to the city from Homewood at the intersection of Montgomery Highway and Shades Crest Road. In 1975, a 150-ton crane, the largest in Southeast at the time, blocked traffic to move the 63-ton, 11.5-foot-tall structure across to its new resting place. At its new home, the Vestavia Hills Garden Club painted the temple, faced the base with brick, laid floor tiles, repaired steps, poured sidewalks, lit it and cleared grounds, and the temple was dedicated in 1976 during the Dogwood Festival.

A Church with a View

As to the rest of the property, a young Vestavia Hills Baptist Church purchased its 15 remaining acres for $140,000, making the front cover The Birmingham News on March 24, 1958.

In the early days, church members would climb circular stairs in the temple to Sunday school classrooms, and the space that had served as the restaurant and dance floor became the sanctuary, with the pulpit on the raised band stage. (Today this space is the church’s fellowship hall.) Some members draped the statues to keeping them from “distracting folks.”

Vestavia HIlls Baptist Church added an education wing onto the building with the temple still intact before the temple, in a state of disrepair, later came down to make way for a new sanctuary.

By 1967, church membership had reached 600, and they were in need of a new sanctuary. Ultimately, the Vestavia Temple itself had become too unsound as a structure to save at a reasonable price, so the church decided to rethink the building. Community members were upset about losing the temple, but its columns were not marble but rather plaster and chicken wire that had been eaten by termites and the statues were not antiques, contrary to popular opinion.

The church advertised the building as “free for the taking” in the Wall Street Journal. Ultimately, however, it was demolished—but not before relics including light fixtures, statues, concrete benches, pews and old books were auctioned off and made $2,971 for the church building fund. The new sanctuary was completed in 1972 over the lawn between Vestavia Temple and Sybil’s temple. Where the Temple of Sibyl once stood, a “Prayer Point” now overlooks the valley with one the best views around and is sometimes host to small weddings. Before the church installed a metal prefab fencing along the bluff, you could access steps that would led to a tile-covered terrace and then down to a burial crypt where Ward intended to be buried.

Today, the legacy of the temple can be seen as you walk around Vestavia Hills Baptist. As its administrative pastor Dennis Anderson points out standing in the foyer, a curved glass wall around an interior garden stands in the footprint of the former temple, and as you walk the circular throughway, you can imagine the grandeur of the temple portico. Further back in the building, you can still touch a part of the original 2-feet-deep stone wall of the temple placed in 1972 construction. The house was sturdy, Anderson points out, it was the columns that were not. The education wing of the church was built in 1961 when the temple was still in place, so it was designed to match the temple’s sandstone. Likewise, all subsequent construction sought to match that design.

For the church gardens on the property harken to creation—but also to the manicured rose gardens, pools and fountains that elevated the original Vestavia to such a status of grandeur. They’re just missing the peacocks.

Editor’s Note: Much thanks to those who helped compile the photos and information for this article: Dennis Anderson, Sara Wuska, Shelia Bruce, Vestavia Hills Historical Society, Frances Poor and George Richey. To learn more about the temple, find these resources at the Vestavia Hills Library in the Forest: Vestavia Hills: A Historical Collection, Compiled by Frances Poor, and Vestavia Hills, Alabama: A Place Apart. Vestavia Hills Baptist Church: The First 60 Years, 1957-2017 by Cynthia Wise Mitchell was also a helpful resource.